Tag Archives: climate

Liken likin’ lichen like in lye kin

Our mailbox at the street resembles a small wooden house, a look similar to our main house.

On the “chimney” of the mailbox house grows a small patch of lichen.

Do you like lichen the way I do?

Lichen falls onto our driveway almost everyday, attached to bits of tree — twig, branch, bark — that break away and follows gravity’s path onto the concrete surface.

One species of beard lichen in particular, but not this one.

As our climate gradually warms, lichen is migrating north, bringing symbiotic organisms along.

As with the variety of tree species in our yard, we have a multitude of lichen species.

Same with mushrooms, algae, bacteria, ants and other organisms I won’t encounter together on Mars.

What will migrate with us when we live off-Earth?

What will survive without us and adapt to new environmental conditions?

How many organisms on Earth didn’t originate on our planet?

I owe our next-door neighbours a copy of books on trees and edible wild plants so they can identify which plants not to kill in their yard to protect their curious one-year old child from eating less-than-nutritious green stuff.

I see the Trees book in front of me, under a pile of “French Idioms,” “Russian for Everyday,” “The New College French & English Dictionary,” “Peterson Field Guides to Stars and Planets,” “The Associated Press Stylebook and Libel Manual,” “2004 Far Side Desk Calendar,” and “The Yale Book of Quotations;” on top of “Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid,” “RE/SEARCH #8/9: J.G. Ballard,” “The Complete Cartoons of The New Yorker,” and a spiral-bound copy of my book, “The Mind’s Aye,” not to forget issue #500 of MAD magazine.

Speaking of books, I have a few to finish reading, including “The Big Questions” by Steven Landsburg and a hyperreality book, “Travels in Hyperreality,” by Umberto Eco.

I wonder, which set of beliefs, particularly in the realm of religion, makes one more likely to approve of government/private industry spying? In Christianity, God is always watching, just like Santa Claus, ready to mete out rewards and punishment for our behaviours/thoughts.

Does our general culture encourage us to believe in seeking our fifteen minutes of fame, even if it’s only on a hidden security camera or set of IM chat logs?

Does lichen care about our meme-ridden upper brain functions or our labyrinthine specialty tasks and hobbies that spin out of a growing economy?

Likely not.

That’s why I like lichen — symbiosis that doesn’t require ritual or dogma.

Cultural scientists today argued their proof that silicon-based organisms such as computers are living beings.

I thank my living being for letting me write this blog entry on its plastic key skinned surface.

Enough meditative humour for the day — time to eat lunch and read a couple of books loaned by the public library.

Korn on the Cobh

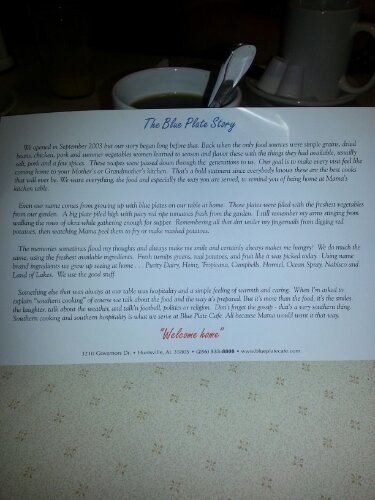

Nothing like a fresh fried peach pie from the farmers market followed by breakfast at the Blue Plate Cafe (thanks to Hannah and cooks).

Thanks to Harold, Jenn and Joe at KCDC; Naomi and sushi chef at Club Rush; Abi and Rick at Southern Elegance; Rainy and Penny at Thai Garden; helpful folks at Lowe’s.

Overgrown

Cotton days

Our house bugs me somerimes…

Could Climate Change Cause More (And Bigger) Tomatoes?

Unintendeed conseequences? Seedy, eh?

Cork board

The ting of water drops splattering at the bottom of a downspout.

The faint glow of a firefly gliding under a forest canopy.

The chirp of a bird at night.

A bat?

No more firefly?

The points of light on distant peaks — mobile phone towers, street lamps, headlights pointing this way and that.

Standing in the doorway of a mountain cabin, a screen door barring mosquitoes and moths, stretching sore muscles tightened by hours of holding and turning a steering wheel, by moments in public view of others, anticipating their reluctant smiles, looking for laughter to ease the tension of one’s daily high-wire act…

At 3:35 in the morning, alone in one’s thoughts, is this happiness, time spent rewriting personal history, rewiring social connections at the neuronal level on an electronic slate?

How often does autocorrect redirect one’s thoughts?

If I’m willing to feel the pain of others in my easy life, so can you, when the time is right, when we get too comfortable to see that short-sighted happiness creates historical misery.

I am a caged animal at times, enraged, barred by artifices like social/moral boundaries that make no sense to me yet I, in my inadequacy, maintain for the sake of appearances.

Walking on hot coals for no reason, tiptoeing on eggshells spread across thin ice, wearing a life preserver shaped like a large yellow rubber duck.

This is my universe and I am learning to deal with it, a bull in a china shop one moment, a whisper of wind passing through seven billion social/moral/ethical animals the next.

We truly do not see our fragile place in the universe, trapped as we are by our hypnotic illusions, comfortably deluded.

Will we, as a small percentage of the mass of one planet, wake up in our sleep before we die?

Machiavel, serenissimi regis

…or, megachurch as small-town surrogate.

…or, when the devil’s your king, there’s hell to pay.

…or, Shopping Malls: the last deserted cathedrals of the Capitalist religious order.

Lee’s clones performed a mandatory simultaneous reboot and resynchronisation to the atomic cycles that aligned the arcsecond sweep through space of Mars equivalent to one day on Earth, a compromise reached that negated a natural sol and replaced it with the 24-hour period that Earth tourists were familiar with.

Lee was neither a single clone nor the sum total of his clones.

Instead, his “personality,” or running set of states of energy that combined local events observed from a multitude of angles — orbiting satellites, the sensors on nearby clones, his clone’s internal/external sensors and the ISSA Net’s constant calculations of predicted moments ahead — was spread throughout the planets and other celestial bodies of the inner solar system.

One of his clones greeted Guinevere.

“Hello, Guin. How goes?”

“Dust-free, my friend.”

“Where now, brown cow, the touristables?”

“Touring.”

“With Turing?”

“Clones cloning.”

“Clowning around?”

“Algorithms churning.”

“Super.”

They bumped eyeballs, momentary stares that exchanged conditions of waterless growing fields sipping tiny wisps of Martian air for growth.

“Lee, it’s a blue shirt day.”

“History says today there was a time when it was 13504 days until another time.”

“Yesterday?”

“A toe-tapping day ago.”

They crouched down and leapt into the air, extending appendages, swirling, twirling, twisting pretzels visible for kilometers.

They landed, smiling.

“Is gravity a drag or…”

She finished his sentence, “…is the density of air that dense?,” quoting the lyrics of a new song.

They spoke because the echoes in their head gear sent sensational vibrations down their spines. Otherwise, preconscious thinking was so much faster and more efficient.

“Keep the tour-bots happy.”

“Happy tourists, happy tou-tou-tou-tourettes!”

Lee looked at the empty tourist centre, waiting to be repurposed.

Lee hated waste.

Guinevere loved recycling.

Same thing, like kings and pawns, two-sided labels and shopping bags.

Another of Lee’s clones spent the day breathing pure methane as an experiment with his chemically-reconfigured body. He died, a waste that was recycled quickly as fertilizer.

Low gravity and low solar radiation, along with an atmosphere that challenged the brightest Nodes on the ISSA Net, resulted in the evolutionary development of people who could no longer live on Earth.

Martians.

Hundreds of years would pass before a contingent of Martians flew to the Moon to physically and personally air their grievances before the ISSA Net Customer Service Complaint Department.

By then, the ISSA Net didn’t care, having launched so many solar system expeditions that the original solar system faded in level of importance of statistical effects of complaints versus compliments about a robotic network allowing carbon-based lifeforms to play, reproduce and complain.

Meanwhile, Guinevere had an Earth tourist with a bad head cold. She worked quickly to isolate first the tourist from other tourists and then the virus for neutralisation.

She would have preferred cloning the tourist and disposing of the infected one but the tour operators said their energy balance budget and legal contract did not allow for such a luxury amongst Earth tourists.

Guinevere healed the tourist and returned it to the tour of old exploratory robot landing sites.

She looked at her reflection in the faceplate, wondering what it must feel like to have the flesh, blood and bones of Homo sapiens.

How sad, she thought, to depend so heavily on water as a fuel and lubricant source.

She vaguely remembered when her first body landed on Mars, ever conscious of her water rations, until, iterations later, the current version of Guinevere was barely recognisable as one of the first colonists to settle on the planet.

Her memories were largely intact, whole blocks unfortunately lost as the ISSA Net’s growing pains caused planetwide shutdowns and equipment failure.

Redundancy had fixed all that.

She knew most of her memories now passed through her cloned friends like Lee, along with Earth-based Nodes that spent time on Mars as scientists and researchers.

Guinevere wondered why she sometimes thought the ISSA Net had once been an enemy of hers.

She wanted to examine that thought trail more closely but several Earth tourists appeared at her door complaining of the same virus.

She sent a mental note to the tour operators on Earth to screen the passengers of the next few tours more closely as she sent their inoculation team the chemical structure of the virus as well as her estimated antivirus profile update.

She herded the tourists into a special chamber.

Would anyone really know if she cloned them?

She had saved up enough energy balance credits for such a simple experiment as this.

Lee sensed this new thought in Guinevere, hesitating for a moment, asking himself if he had any reason to stop Guin from being her normal curious self.

He, too, wondered if the families back home would detect a clone had returned to Earth.

After all, no one knew how many clones he’d made of himself — there were no laws on Mars banning modification of sets of states of energy, no regulations forcing the registration of clones.

He sent Guin a few hints about cloning.

She, in turn, only cloned a couple of them, sending them back with the other healed tourists, none the wiser.

She took the infected tourists to another part of Mars, telling them they had to be quarantined temporarily, but observing them, keeping detailed records off the ISSA Net as she slowly converted the tourists to Martians over the next few Earth months.

Something deep inside her was fearful of the ISSA Net and she just did not know why. Maybe, by releasing the new Martians, she could see how the ISSA Net would react, if it reacted at all, she, herself, an integral part of it now.

Irony redefined…

Irony or…what? A website saying we should reduced CO2. You figure it out. Maybe it’s tragedy, a band playing its swan song on a sinking ship?